Hot Dogs and Cultures: A Case Study

I've been meaning to write about this for a while. This isn't going to be a technical post or a post better explaining technical or business terms. This is literally going to be case study of hot dogs among a couple of cultures. So, buckle in, and thank you for indulging me here.

A brief history of the hot dog

According to the State of New York's taxation code, a hot dog is a type of sandwich yet the Cube Rule of Food clarifies that a hot dog is, in fact, a taco. How can this thing be so divisive? Well, that comes from murky origins.

It's generally accepted that a hot dog is a type of sausage in a bun (though I am certain some purists will be by to correct me). It's an assembled, portable meal to go. Any condiments you add to it keep it a hot dog, such as ketchup or mustard. So how did this little cornerstone of American food get started?

The type of sausage included in the bun is either a Frankfurter or a Vienna Sausage (a wiener) - which is a good way to tell it's German in nature. Indeed, the National Hot Dog and Sausage council notes that the city of Frankfurter celebrated 500 years of this particular sausage being produced in 1987. As of writing this, that means the sausage part is roughly twice as old as the United States of America and created during the rule of King Henry VII (the father of the infamous King Henry VIII). I think we can give Germany the win on the sausage part here.

However, in 1871, a German immigrant and baker in Coney Island is said to have sold 3,600 sausages in "milk rolls" that year marking a good entry point and leading up to the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago.

The 1893 World's Fair, technically the "World's Fair: Columbian Exposition", introduced a number of things as "Firsts" - Cracker Jack's debuted their new (successful) snack, the Ferris Wheel, the brownie, the first commemorative stamp set, and Pabst Blue Ribbon among others. However, the important note here is that Vienna Sausage (now since renamed to Vienna Beef) vended many of their Frankfurters in a bun, near the entrance. It was a huge hit and with many international and domestic visitors, it sealed the Vienna Sausage as "Chicago's Hot Dog".

Parallel in 1983, a baseball team owner of German descent started to sell hot dogs at his team's stadium, and it quickly spread to other stadiums as a quick and cheap food to sell to those going to games. The proximity of the St. Louis Browns to Chicago likely was also influenced by the World's Fair, or the other way - unfortunately, a nuance not yet studied by hot dog historians.

So, now that the hot dog is normal and likely launched significantly from Chicago and St. Louis, what happened next? 1929.

The Chicago Dog

For those to whom American History is not a common subject to study, 1929 was when the American economy crashed. Many factors led to it which I'll leave to others to explain, but of import is that many Americans were out of work and destitute. It was a rough time for American families to simply feed themselves, let alone companies maintaining restaurants to survive. The cascading effects left many people scrimping and saving everything into a "poverty mindset". Which, in turn, caused businesses to adjust to better serve a crowd that could no longer afford things they had a decade earlier.

A now defunct food stand called Fluky's created the "depression sandwich" which consisted of a hot dog on a bun covered with mustard, pickle relish, onions, a dill pickle, hot peppers, lettuce, and tomato. The hot dog was a very cheap meat yet was still a potential source of nutrition and protein, a good food for a time when the American economy was nearly non-existent. This depression sandwich cost a nickel - not an unreasonable price at the time for a treat. A generation grew up with this as a notable food source, especially in Chicago. Due to an invention in the 1860s, producing tubes of meat from the "extras" of the famed butchers of Chicago was automated, quick, and low overhead - meaning people near Chicago could maintain a cheap hot dog fueled diet. The American economy slowly recovered, but the poverty mindset persisted through this time, making hot dogs and "depression sandwiches" a common staple.

In 1941, the US entered World War II and four years later, American soldiers returned back home. Despite being abroad, most had consumed military rations and not the fares of foreign lands they fought in. When they returned, they wanted the comforts of home, which in Chicago area included the depression sandwich. Hot dog stands popped up all over Chicago in the post World War II era, converting the "depression sandwich" to the Chicago-Style Hot Dog (and losing the lettuce along the way).

Due to this resurgence, and smart pivot to "Chicago-style" for branding, it became an icon of Chicago. In fact, if you go get a hot dog in Chicago and ask "for everything" or to have them "drag it through the garden" you get:

- A poppy seed bun

- A Vienna Sausage (or other beef hot dog)

- Neon green pickle relish

- Pickle spear

- Mustard

- Raw onion

- Tomato slices

- Hot peppers (sometimes called sport peppers)

- Celery Salt

An aside, why is the relish dyed to look almost like nuclear waste-flavored? Back in the times of the black-and-white photo, the contrast of the normal relish was decidedly unappealing, so the Vienna Sausage company dyed it to give it vibrancy, and this carried into modern times.

No lettuce, no ketchup (and in modern times, asking a Chicago hot dog vendor for ketchup is almost as bad as insulting someone's mother), but most importantly, forgoing any ingredients makes you seem like an outsider. "True Chicagoans" eat it all - and growing up, this is how I also ate them. I really don't like anything pickled so two kinds of pickled things on it was gross, but it wasn't really presented as an option. Even today, I will avoid pickles and pick them off things, but not off a Chicago dog.

When I introduce people who know my taste preferences to Chicago dogs, they are often surprised by my consumption of the pickled good and the insistence that, forgoing any allergies, they do the same. Much like something like sushi, the experience is not the parts but the sum of the whole hot dog - or at least what I tell myself. Likely, I am just a snob, but it is part of how I grew up.

So, I promised cultures, so let's rewind back to World War II a moment, and take a different angle.

Pylsa (Icelandic hot dog)

Note to any Icelandic readers: I am not a native speaker and am not qualified to really dive into the Pylsa v Pulsa debate. I am going to lean on Háskóli Íslands and will ask that you go yell at hola íslenskra fræða to sort this out further.

The Icelanders have their own hot dog, translated as a pylsa. At its core, it is a hot dog - it's a type of sausage in a bun. However, unlike Chicago or the United States, Iceland isn't awash in cow or pig farms. The hero of Icelandic cuisine and clothing is, instead, the sheep. Starting with the inception of the major meat producer in Iceland in 1908, they've been making hot dogs with lamb.

However, World War II left Iceland in an interesting spot. It is not a heavily populated country, but is well situated as a way-point in the North Atlantic and a potential risky "back door" to the Allies. The country was technically under Denmark as head of state, but was a sovereign kingdom. Despite Denmark being occupied by Germany, Iceland declared itself neutral and technically maintained this neutrality through the entire war. A lot of important details aside that I implore you explore about Iceland in World War II, the British "invaded" in 1940 and before the US got involved in December of 1941, they assumed the role of defending Iceland from "outside forces" in July of 1941.

Remember Americans really having a thing for hot dogs so close to the Great Depression? Great, you can probably guess where this is going.

Iceland is not a hospitable place to grow things like cucumbers, and definitely not in the mass quantities to make it a cheap food. Even today, Iceland imports a significant amount of vegetables and flowers from mainland Europe. However, hearty plants, like onions grow in Iceland as do tomatoes (to the point there is an excellent tomato-everything restaurant, where everything has tomatoes, even the beer). Other things hard to grow in Iceland? Corn and sugar cane. Which means they get to be smarter about trying to recreate international foods locally. Although flour rationing was in place until 1948 (and thus hot dogs were served in paper, instead of a bun), by 1950, an undyed lamb hot dog nestled in a bun with onions became more common. Their tomato ketchup? Sweetened with apples instead of corn syrup or sugar. Remolaði? This concoction of mayonnaise and pickle relish and other flavors suit the Icelandic palate while still offering a slight pickled taste. They even have slowly created their own hot dog mustard, Pylsusinnep, which is an explosion of flavor compared to the boring yellow mustard of the USA.

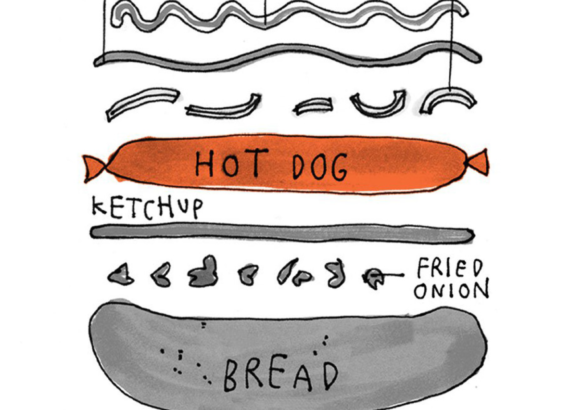

Much like a Chicago dog, the Icelandic Pylsur is best eaten as a sum of it's parts, which is, from base to top:

- Steamed bun

- Fried onions

- Ketchup (sweetened with apples)

- A lamb pylsur (steamed, never boiled)

- Raw onions

- Mustard

- Remoulade

And is this layering important? Yes, yes it is. Again, I'd rather argue the ratio of malt soda and orange soda for their Christmas drink than violate this layering technique. Should you try it this way? I'd argue yes, but at least one famous hot dog connoisseur ordered it with only mustard.

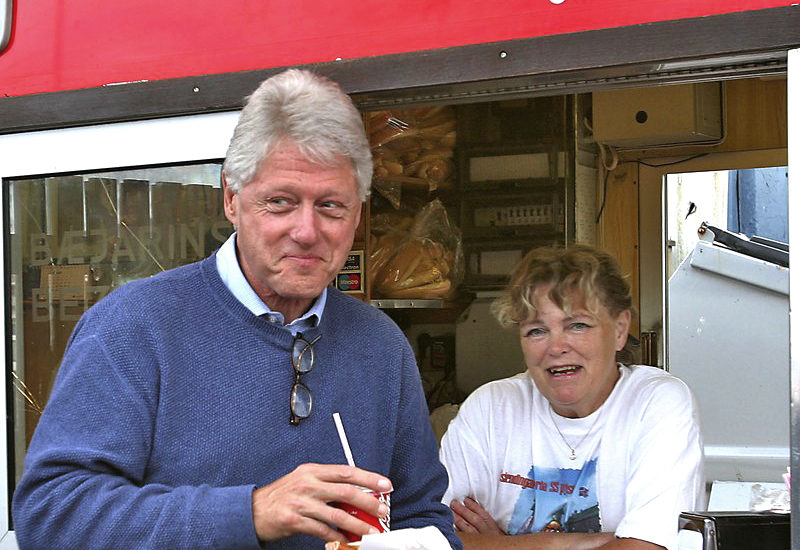

How much of a cultural thing is this hot dog? Beyond the 42nd President of United States visiting the most popular stand in Iceland, Bæjarins Beztu Pylsur, a number of famous people have gotten one when visiting, from Metallica's James Hetfield, Kim Kardashian, author John Green, to even food travel documentarian and chef Anthony Bordain.

When ordering one, please order "eina með öllu", or one with everything. The collective mockery of ordering "eina Clinton" is still a bit of shame for American tourists. Curiously, it is also one of the cheapest foods you can get, at 600 ISK (about $5 USD at time of writing this) where other street runs closer to 2200 ISK in most of Reykjavík. A bit of carry over from when it was a cheap food for people during the war to now, but one that I enjoyed during my last visit.

Comparison

At a high level, we have two very different hot dogs - one made of lamb with two kinds of onions and three sauces, the other made of beef with an entire assortment of vegetables. However, due to cultural and geographic development, we see that they came to their end with different reasons, giving each culture a shared core and yet a distinct, identifiable food. If I went even more in depth, we could speak of New York style hot dogs, or Korean street food hot dogs, or the others created across the world and how they came to be.

Which do I prefer? Honestly, they each fulfill a different situation for me, but Chicago dogs are easier to find here in the states and therefore my go to, which just makes a visit to Reykjavík more exciting for me and the pylsa the cherry on top - or perhaps the "rúsínan í pylsuendanum" - the raisin at the end of the hot dog (even though there are no raisins in hot dogs, but that topic is more about the influence of the Dane on Iceland definitely outside the scope of this particular study)

Further Study

Seriously, have a good hot dog story from where you're at? I'd love to hear more. Maybe I will get to yet try cultural hot dogs from all over and find further yet a reason to be upset when people simply boil them.

Thanks

Thank you Timothy Hunt for offering some post-publish proofreading and corrections!